Since the days of the apostles, Christians have often found themselves opposing unjust laws of government, especially laws that infringe Jesus’ command to: “Go therefore and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, and teaching them to obey everything that I have commanded you.” Matt:28:19-20. The response to the state in such matters has always been the same: “We must obey God rather than men.”

A hundred years ago, Catholics battled to the U.S. Supreme Court in Pierce v. Society of Sisters, for the right to educate their children in parochial schools.

In recent years, mandatory child-abuse reporting laws have required clergy members to report confidential admissions of child abuse to government authorities. Such laws may now require priests to divulge information in violation of the seal of confession. Similar efforts have been made in other countries.

There currently seems to be a standoff as governments have been reluctant to enforce such reporting laws because they know that the defendant (priest) will almost certainly risk prison rather than violate the seal of confession. Common sense suggests that the first such prosecution will come—not as a result of any child abuse—but via an undercover cop giving a fake confession for the purpose of entrapping a priest. Eventually, that cop will team up with some attention-hungry prosecutor and we will see how such a gross and foolish overreach by government pans out. Another such overreach happened 160 years ago. That is the subject of this post.

Swearing Loyalty to the State

It was the summer of 1865. The American civil war was over and the radical reconstructionists held the state of Missouri tightly. A new state constitution, the “Drake” or “carpetbagger” constitution, was forced on the citizens, narrowly passing by a margin created by the “yes” votes of the occupying Union soldiers. The purpose was to punish–and remove from public view–all those who had favored the southern cause in the newly-ended war. The new constitution required a loyalty oath to the United States in which the oath-taker swore that he was loyal to the Union during the war.

Giving aid and comfort to the enemy and avoiding the draft were cited as disqualifiers, but the oath went much further. Anyone who had ever made a mere suggestion of sympathy with those engaged in the rebellion were considered disloyal. An example of such disloyalty was seen in a man who had brought his dying confederate brother home for burial. No one was allowed to vote without swearing the oath.

No preaching without taking the loyalty oath

The state of Missouri made it a crime for any officeholder, lawyer, teacher, corporation director/manager or member of the clergy to practice their profession after September 2, 1865, unless they had taken the oath. Missouri Gov. Fletcher took a hard line on enforcement, suggesting that the state penitentiary at Jefferson City be enlarged to accommodate all the clergymen and teachers who refused to take the oath. See Donald Rau, “Three Cheers for Father Cummings,” 1977 Yearbook, Supreme Court Historical Society.

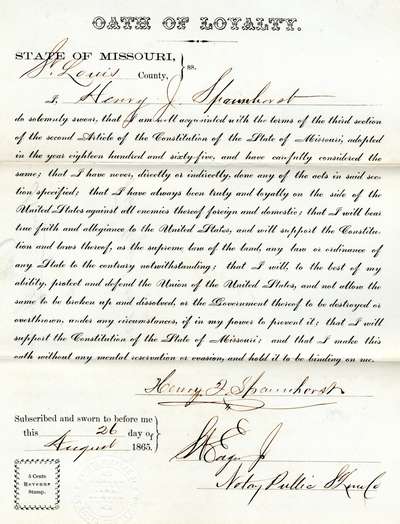

Here is an example of the oath that was required.

Click here for a hi-res copy of the 1865 oath of Henry J. Spaunhorst.

Archbishop of St. Louis, Peter Kenrick, viewed the oath as an infringement of religious liberty and determined to resist. Believing the oath to be unconstitutional, he instructed the priests of the state not to take the oath, saying “The next thing we know, they will be dictating what we shall preach.”

Father John Cummings defies the state

On September 3, 1865, Father John Cummings, the young pastor of St. Joseph Catholic Church in Louisiana, Missouri said his regular Sunday mass and preached from the pulpit. He had not taken the oath. The next morning, a grand jury—convened under Judge Thomas Fagg—indicted Father Cummings for preaching the Gospel. A contemporary account takes up the story:

“[A] Radical Sheriff, one Wm. Pennix, . . . once a strong pro-slavery man, arrested Father Cummings and lodged him in jail, consigning him to the ‘felon’s cell’ and the association of thieves. Said one of the felons to the priest as he entered the cell, “What are you put in here for?’ ‘For preaching the Gospel,’ replied the priest. ‘Good,’ said the man, ‘I am in here for stealing horses.”

“The arrest and imprisonment of Mr. Cummings produced vast excitement. Men and women crowded around the jail, and the commotion was so great that the Judge and his men were anxious to bail him out, but he would not be bailed out. Then they were anxious that he should run off, and gave him a chance to do so, but even this poor boon he declined, preferring to remain in jail. In a few days Archbishop Kenrick, of St. Louis, sent up and had him bailed.” W.M. Leftwich, Martyrdom in Missouri, 1870

Conviction and Appeal

Soon after, Father Cummings appeared before the court. He pled guilty to preaching without taking the oath, but complained that the law was wrong. Fagg accepted the plea and readied to sentence the priest. The proceedings came to a sudden halt, however, because a solidly pro-union lawyer and U.S. Senator from Missouri, John Henderson, happened to be in the courtroom that day on other business. Henderson rose and objected, pointing out that Father Cummings had actually pled “not guilty” since he claimed the law was invalid. The court had to agree and allowed withdrawal of the guilty plea. A bench trial was held and Judge Fagg convicted the priest, sentenced him to pay a $500 fine and to be held in jail until it was paid.

“It was to be another day of surprises for the Radicals. Much to their chagrin, Father Cummings refused to pay his fine or to post bond for an appeal, and refused to permit anyone else to pay his fine for him. The reaction of Father Cummings’ parishioners at Louisiana must have added considerably to the discomfort of the Radicals. They refused to accept the imprisonment of their pastor without protest. “Father Cummins’ [sic] parishioners came up from Louisiana, and camping about the dungeon of their beloved shepherd, were in much the same frame of mind as the children of Israel when they set down and wept by the rivers of Babylon.” Rau, “Three Cheers for Father Cummings.”

The Catholic priest remained imprisoned in the Pike County Jail at Bowling Green for more than a year, while his conviction was affirmed by a Missouri Supreme court (just fifteen years after that court’s decision in the Dred Scott case). With the support of Archbishop Kenrick and the assistance of nationally respected lawyers, Cummings finally won his freedom in the Supreme Court of the United States.

In addition to denouncing the odiousness of all loyalty oaths, the court noted that other countries at least limit their loyalty oaths to contemporaneous conduct, but here “the oath is directed not merely against overt and visible acts of hostility to the government but is intended to reach words, desires, and sympathies, also. And, in the third place, it allows no distinction between acts springing from malignant enmity and acts which may have been prompted by charity, or affection, or relationship . . ..” Cummings v. State of Missouri, 71 U.S. 277 (1867).

The Court found the law to be an unconstitutional ex post facto law enacted to punish past conduct that was not a crime at the time. The Court also held the law to be an unconstitutional “bill of attainder” which is any legislative act which inflicts punishment without a trial. Father Cummings was then released and resumed his duties.

Other priests and ministers had also been convicted under the law and some of those also imprisoned for a time.

Missouri’s second-most famous Supreme court litigant died young, just ten years after his famous defiance of the state. Father Cummings is buried at St. Louis, Missouri in Calvary Cemetery, just 500 yards from Missouri’s most famous litigant, Dred Scott.